- Home

- Michael Ruffino

Adios, Motherfucker Page 11

Adios, Motherfucker Read online

Page 11

“Or the other one. Back and Forth. Either one is fine.”

“With that cover. That girl, that hot dog, all that.”

“Yes,” said Clem. “I could do that. Because that works. See?”

“I’m ninety-nine percent sure this is the most ridiculous conversation I’ve ever had in my life,” Matt said. Which was saying something.

“Well, that’s the choice. You let me know.”

Down on the street, Matt said, “Did that just actually happen?”

“Of course not,” I said. “We’ve simply forgotten we took a shitton of acid. We’ve been having a joint hallucination. In reality we’re sitting on a bench downtown right now, drooling and looking crazy.”

“I should fucking hope so,” Matt said, flummoxed.

A bike messenger coasted past us and cornered onto Park Avenue. He didn’t see the taxi speeding out of the tunnel like a cannonball. I doubt he lived long enough to know what hit him.

The album remained in limbo. Proceeding under the current arrangement was out of the question. On the other hand we had almost no trouble booking anywhere now. We sold out the Continental, a line of people out the door, almost to the sunglass swami at the corner. Not a big place, just another dive off St. Marks, but we’d moved up a rung. My parents were at the show, a sea in the drunken throng. My father improvised earplugs using toilet paper, extraneous sheets hanging out of his ears, a Sicilian rabbit. Matt drank an entire bottle of Robitussin before we went on and had to excuse himself twice during the set to go downstairs to the bathroom and throw up, while Eugene and I vamped and told jokes.

We hadn’t been banned from anywhere in ages when the planets aligned at a place called Arlene’s Grocery over on Orchard Street.

Matt had resigned himself to playing a guitar he’d found in a dumpster earlier in the day, with rusted pickups and one string on it, and we limited the set to songs we’d never played before and songs we hadn’t written yet. The exact reason the club shut us down wasn’t clear, though when it happened the soundguy, or manager, or somebody, berated us at length over the PA. I missed that part, I was testing out a borrowed wireless system, standing on top of a car parked across the street, playing an open E. Someone came over and told me the show was over, the club had cut the power. The whole thing was beyond chaotic, a first-rate disaster, even by our standards.

Lenny Johnson, an A&R executive, had made every effort to time his arrival to avoid having to witness our set. (A&R are the people at record labels who scout and acquire acts, and oversee any development once they’re signed. Originally, “artists and repertoire” men, who matchmade singers and songs; these days, short for “airports and restaurants.”) Lenny had seen us once and, he told us later, that had been one time too many. He was there to see the band we were playing with, called Hot Water, a band Beaver had turned us on to. Two brothers, Jaime and Lou, good men, kind of a Creedence Clearwater vibe; we liked them. They had actual talent, as opposed to making a show of your inability to take care of yourself that often masqueraded as talent on the Lower East Side. Jaime and Lou were being wined and dined regularly by A&R people from several big record labels—“courted,” in the parlance. Just as in the dating context, it was a matter of decorum that a major label took you out to dinner a few times before it fucked you.

The show that night strayed further than usual from the schedule, and Lenny accidentally caught our set. The next day we were in his office talking about a deal.

The label Lenny worked for was called TVT, an acronym for TeeVeeToons. The president of the label, Steve Gottlieb, built the company off the small fortune he made selling CD collections of classic TV theme songs with lapsed copyrights—Gilligan’s Island, The Addams Family, Dragnet, many more—out of his car, and used some of the proceeds to buy Trent Reznor’s publishing rights and release the first Nine Inch Nails album, which became a megahit. TVT was in a new category of record label—the “major-indie,” autonomous, with a lot of capital. Lenny was head of TVT’s A&R department and had a good track record. His boardroom pitch to sign us to the label did whatever it needed to, and not long after, TVT rented out the upstairs of Coney Island High for us to play a private showcase for the label staff and Gottlieb.

We did our thing; too loud, shit falling over, blood, nudity, huffing amyl nitrate every two minutes, so on, and passed the audition.

The next morning we were with Miss Management, Beaver, and Lenny in Gottlieb’s corner office at TVT. Gottlieb pony-tailed and beaming behind his Swede command center. The contracts had been negotiated, everything was in order, the only loose end was that we needed to get legal possession of our masters from Clem and Payola before we could actually sign anything with TVT. Recovering our masters would almost certainly get more expensive if foundering Payola learned that a moneyed interest on the scale of TVT had entered into it, and our mid-six figure deal on the table was contingent on those album rights. I was pretty sure we could get Clem to comply, at cost, if we played dumb. A plan was hatched and Gottlieb pushed a button on his desk phone. A little while later an assistant walked in with a generic bank check, the exact amount of Payola’s investment. I took the check and folded it over my waistband (leather pants, no pockets) and we walked out the door.

(Lenny told us later that after everybody left Gottlieb was giddy, “Like a kid almost,” but not long after rang Lenny in his office, extremely concerned, after it had sunk in that, shrewd as he was, he’d let a notoriously booze-guzzling, drug-sniffing, possibly idiotic, rock trio loose in lower Manhattan with a bank check, without signing anything, not even a receipt. Lenny assured him it would be all right, that we were the nice guys Gottlieb thought we were. And again each time Gottlieb checked back.)

I called the Payola offices from a pay phone outside the nearest bodega. I told Clem a relative had died (not specifying, superstitiously), and this relative had left some money that we wanted to use to buy back our master tapes, that that’s what this relative would have wanted. As we’d banked on, Clem saw no value in the music beyond Payola’s investment, and agreed to return the tapes at cost. We’d forgotten to ask anybody for subway fare, so we walked fifty blocks up to the Payola office (hence the sweating back at TVT), where Clem signed the appropriate papers. We made businesslike small talk, swapped the check for the reels, shook hands, and left Clem as we found him, with eight thousand dollars and zero sense.

We rode down in the Payola elevator, hoofed it the fifty blocks downtown, rode up in the TVT elevator, dumped the master reels with Lenny and the visibly relieved Gottlieb, doffed our invisible bowlers, and went out and got hammered to transcendence. As you do.

13

TEE VEE TOONS

MONDAY

8:02 A.M. . . .

Reclining last night on the backseat of Lenny’s convertible Chevy land yacht, contemplating the tiles on the ceiling of the Lincoln Tunnel on the way back from another meet-and-greet swill-o-rama at someone’s minimansion in Jersey. A cookout, complete with lawndarts injuries, lighter fluid flamethrowers, someone (not our crew, for once) projectctile vomiting onto a veejay, rent-a-cop hassle—just like a regular, non-professional cookout, though technically speaking we were at work, doing our job. Racking up overtime lately, really putting our backs into it, noses to the grindstone, presumed to be beneath the sedimentary layer of coke. This continuous wine and dine, getting to know people from each department at the label and what they do (these meetings tend to devolve beautifully); Bacchic introductory meetings with music publishers, marketing “geniuses,” producers, radio promo guys, distribution guys (true operators—the lowdown on how a CD is wrangled into a specific slot in a Walmart display rack, and a corresponding crack in the consumer psyche, is low down indeed). No end of information coming at us over angelic organs of empty highballs, goblets, tumblers, as filets are inhaled; no shortage of parties (obligatory hobnobs can more often than not be upended into genuine throwdowns), a slew of things we need attend to during business hours, most scheduled to

o early for us to bother going to sleep—not that there’s a set place any of us do that when in New York. I was camped on Erin’s couch for a time; once and a while, on take-your-broke-ass-rock-inebriate-to-work days, I guess, I’d go with her to her office, a formidable PR firm, midtownish, where she’d have me do filing and mailing, and sometimes chip in writing press releases and toilsome artist bios until it became clear it was time for me to extract myself (too late, I’m sure). Matt’s still holding a set of keys, but at a price, so most of the time we’re still winging it at three A.M., minus the existential dread and half-blind panic of the darker, record deal-less, era immediately previous. I woke up strangely refreshed under an ample dwarf spruce somewhere in the Twenties the other morning, and a wino domiciled under a neighboring shrub did a Vanna White handsweep around his arrangements and said, “Not the Ritz, but not bad—right?” Weak comparison notwithstanding, he was on an upswing too, and I agreed with him. These circumstances might not look so promising to the average respectable citizen but I’ll say this: knowing there’s a legal document in existence that says we’re legit, and we will thereby henceforth and forthwith, in accordance with the laws of the State of New York, be afforded the means and opportunity to make a living playing music does a hell of a lot for the worldview, and no nightstick jabbing at you through the local flora can do anything to scramble it. Fucking A right, I’ll move along.

We were in the label war room yesterday afternoon (Matt showed up with a six-pack, possibly pushing it) for a debriefing on the label’s plan to try and “break” us. There’s no doubt “break” as it pertains to horses, housepets, and spies figures in, but more directly what’s being strategized is how a scrappy hard rock band achieves “mainstream visibility,” and significant “unit shift” (album sales) in a “market climate” dominated—no, tyrannized by boy bands, R&B megastars, and “crossover” gangsta rappers. From a certain standpoint, this is a rough time to be a hard rock band, of any stripe. An electric guitar heard on the radio is almost always: one, a sample; two, a feeble accessory to more unthinkable histrionics from Matchbox 20 or Creed; three, drop-tuned, thoroughly de-sexualized nü metal wanking; or four, the zombie Jimmy Page voodoo-manipulated to piss on his own grave by a mouthbreathing imposter who answers to “Puff.” And close your eyes and hit “seek” on a car stereo—it could all be the same station. Hence Lollapalooza, this massive alternative music festival, had to be canceled—there’s no alternative to anything. As for the corporate merger, this continental collision we keep hearing about, involving Seagram’s, the Canadian liquor giant, and Universal Music, most people we talk to say anybody currently working for or signed to a major label or a subsidiary, who is in the least bit marginal vis-à-vis this new megacorp’s stock prices, is fucked. Fired, dropped, shelved, taken out back and shot, who knows. It’s a safe bet the playing field will become narrower still, and much more expensive—meaning the current “market climate” will likely also be the future one. Then there’s the Internet wild card. All of this was described with flow diagrams and free-floating geometric shapes with spokes leading to question marks on the whiteboard at the far end of the boardroom. It looked like something Kandinsky might have tossed off while sniffing glue with the Riddler.

In short, the label will put us in front of as many loud music fans as possible, we should “just keep doing what we do,” which according to our publicist, Consoli, is now referred to as rawk, as opposed to rock, for some reason. Also noted, if I’m reading between the lines correctly: don’t bring a six-pack to boardroom meetings.

So I was reclined in the Chevelle . . . examining all of that, visually, superimposing it on the undulating, shifting, ceiling tiles of the tunnel, druggily fitting pieces together—we were “rolling,” as the kids say (a more hallucinatory experience than I expected), through a light rain that tasted exactly like gasoline. The last time I ingested automotive fluid, Matt had mistakenly quaffed antifreeze instead of spring water from the nearly identical jug next to it, so I did too. To show him it would be all right. I think. Anyway—looked down over the side of the Chevelle and it was pissing gas all over the tow truck platform and streaming out in our wake (of course it wasn’t raining in the tunnel). A motorist down there speeding up to the cab of the tow truck, honking and yelling. The tow guy pulled over as soon as it was safe, which it most certainly wasn’t, then he got out of the truck and commenced a highly regional shitfit, apparently unconcerned about getting creamed by traffic. Lenny handled him while we climbed down, hailed a passing stretch limo, and got in. Eventually Lenny got in. “You couldn’t have flagged down a cab?” Matt, freshening our drinks, said, “Coulda, woulda, shoulda,” though only the first one was true. The limo had the full, greaseball, prom package going on, synchronized lights, thumping bass, wet bar complete with diabolical premixed cocktails. Easily room for a dozen more people in there, so we picked some folks up along the way, at a red light, then drove around the L.E.S. for a while, picking up more. Nobody we knew, or are likely to see again.

Debarked at cockcrow on the corner of Third and C arms full with what was left of the limo’s bar. The sun coming up fast, and something mechanical about it. As if the limo, hovering off on its underglow—containing a not entirely pleased Lenny, his soon-to-be-date-raped company AmEx, and a lone bottle of birthday cake-flavored vodka—was tugging it into place by some invisible pulley system. Though just then that system was not so invisible.

WEDNESDAY

Remixing the album plus some recording up at Avatar, formerly Hit Factory, with Kevin Shirley, South African guy (Black Crowes album, Iron Maiden, everybody). Stories. New, rarefied world, where all equipment works, you have to expressly ask for bad food if you want it, and when you need something—book, a particular soup from a place upstate, Zimbabwean newspaper, kidney—you press a button and a chirpy assistant appears, practically bouncing off the walls to get you what you need. It’s only visitor’s access to this place that we’ve been given; chaperoned, conditional. Forget that too many times and it all goes away—fact.

Recorded two songs (label hears singles, of some kind), new version of “We Like to Drink and We Like to Play Rock and Roll,” which we made up on the farm however many years ago, the day the chickens all got diarrhea, and a new one that came out fully formed including lyrics and a bridge, when we were checking our headphone mixes; as happens. (Us: “Maybe we should record that.” Kevin: “You just did.”) Matt titled it “Too Much Is Never Enough.” (He has no idea it’s the old MTV slogan. The same way in his lyrics to “Pink Slip” a pink slip is a resignation notice, instead of an official dismissal. And why would he know? None of his business, is the beauty.) We stacked I don’t know how many guitar tracks on top of the basics, all of us playing the same thing, and Matt did one of his woozy leads over the middle section. These are typically hard to improve on, but in this case instead of going out last night (well, a little, after) I worked out something else, a melodic thing (the starting point George Harrison, haywire from there) and recorded it the next day on a studio loaner guitar that cost as much as a modest home in the Adirondacks. Matt showed up for the final mix and preferred his solo. The first incident in a dozen years that approached a creative disagreement. Incident is too strong a word. Kevin stood firm for mine, more firmly than I did, and in the end we left both solos in, all jumbled together, all screwy Tweedledum and Tweedledumber. In keeping with the song title.

MAY 4

Picked up the van, a Chevy conversion, a hair under budget ($6,500). White, tan interior. Enter through the sliding door into the main living area slash media room with two captain’s chairs and the TV cabinet (mini TV, like an AV monitor). Off to the left a bench seat that converts to a bed at the touch of a button (bets on when that will stop working), if you take a right it’s just a short hop to the cab. Recessed lighting, tinted picture windows, shaggy carpeting, fake walnut trim—it’s estate-like—a vansion. Two cymbals, medium-okay ones at that, drained the rest of the funds.

; Publicity department seems to be in agreement that we ought go with the story that Retarder is a lost album, actually recorded in the seventies. The tack we’re to take with interviewers, then, could be that as toddlers we were into booze and crack at least as a point of reference artistically. Or we could maintain that we’re all well north of forty years old. Or we could run with the story that The Unband is a Menudo situation, a franchise, and we’re not the original members. No question this is a terrible idea to begin with, too absurd even for us. Matt was against it. I said, Beezlebub POV, that considering all we’ve ever done in interviews is try not to be interviewed, we might as well be doing a bit. Particularly since all interviews with any loud hard rock band these days are the same (Is rock making a comeback? Why did rock die? Did rock ever really die?). But Matt’s right, it’s no good. We won’t do it. However, if we change our minds we should do the one where we’re druggie babies.

Great White and Dokken tonight. House of Blues. If this were 1986 we’d be at the enormo-dome. I expect a lot of overstretched Spandex.

MAY 5

Thinking about this kid we had in junior high who demanded everyone call him Don Dokken and threw a fit if you forgot, and you refused at your own peril. Not simply “Don,” either, or “Mr. Dokken”: “Don Dokken.” Five-one, maybe eighty pounds wet, this kid, and having a hard enough time as it was. I tried to befriend him one day after gym and realized the extent of the problem when he went on about his process writing “Breaking the Chains.” He was unendurable. I happen to be sitting about five feet from Don Dokken, the real one. He looks a little like Nigel Tufnel mixed with Van Morrison. Seems pleasant enough.

Fifteen-dollar drinks and salmon on a plank—the House of Blues could be a lot bluesier. Heineken bottle caps nail-gunned to the furniture and “voodoo sea bass”—no. I remain unconvinced that “the Blues” is theme-restaurant territory, and that there’s any tradition being preserved here other than ones that originated with P. T. Barnum. As long as it’s just bullshit anyway the place would do a lot better to replace all the arty-crafty furniture with fruit crates to sit on. They could serve two-dollar Ball jars of bathtub rye, then just after you go blind a pregnant woman comes in and shoots you.

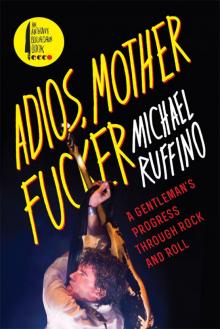

Adios, Motherfucker

Adios, Motherfucker