- Home

- Michael Ruffino

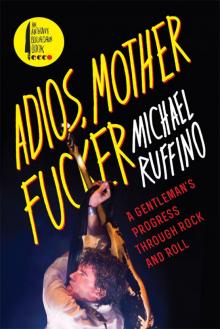

Adios, Motherfucker

Adios, Motherfucker Read online

DEDICATION

FOR THOSE

ABOUT TO ROCK

EPIGRAPHS

Behold with what companions I walked the streets of Babylon, and wallowed in the mire thereof, as if in a bed of spices and precious ointments.

—St. Augustine of Hippo, The Confessions of St. Augustine

All this happened, more or less.

—Kurt Vonnegut, Slaughterhouse-Five

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraphs

Author’s Note

1. Fallen Angel

2. The Connection

3. An Unband

4. Good Music

5. A Census-Designated Place

6. Secondary Education

7. The Old Hotel

8. Recreational Vehicle

9. Unwelcome Home

10. West Coast Idea

11. Pox Americana

12. L.E.S. Is More

13. Tee Vee Toons

14. Thank the Little People

15. Everything Louder Than Everything Else

16. An Unband Abroad

17. Wunt Dunt Dunt

18. Swag

19. Book of Magica

20. Compound Fractures

21. Rock! Rock! (Till You Drop)

22. You’ve Got Another Thing Coming

23. Headstones

24. Snowblind

25. Birthday Spankings

26. Face the Music

27. New Colossus

About the Author

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

AUTHOR’S NOTE

There was a time when people were in the habit of addressing themselves frequently and felt no shame at making a record of their inward transactions. But to keep a journal nowadays is considered a kind of self-indulgence, a weakness, and in poor taste.

—Saul Bellow, Dangling Man

The following pages are a personal record of a rock band from Massachusetts called The Unband, pieced together from journals, tour diaries, and miscellaneous scraps written between 1987 and 2007, or thereabouts. A couple of the tour diaries included originally appeared as features in New York City alternative weekly NYPress (defunct) as “Tour Diary: The Unband, On & Off the Road” (2000), and “Almost Infamous: The Unband/Def Leppard” (2001), and were the basis for a 2004 book called Gentlemanly Repose, comprised of the same source material used here. Where that book was true, the way an inkblot is truly a cigar-smoking rabbit with alligators for arms, this one means to present things as they actually happened. When my written record was unclear (indecipherable, ridiculous, etc.) I often crosschecked my recollections with other people’s memories, reviewed video footage, correspondence, print articles, tour itineraries, and other documentation, keeping in mind that facts, like odds, and sound advice, were anathema to The Unband organization such as it was, and were chucked out the window of a speeding conversion van as summarily as cashed vodka bottles, video footage, correspondence, print articles, tour itineraries, and other people’s memories, and that dispatches from said speeding van, while rolling down the window, or doing the chucking, form the core of the text here. Still, I did go to some lengths (microfiche) to be true to my school, so to speak, and to avoid misrepresenting anyone involved.

Certain chronological details have been tinkered with, to compress time, and because the actual order some events occurred is simply not believable; along the same lines I’ve taken small liberties combining details of some live performances to illustrate what was in reality a cumulative effect (e.g. getting ejected or banned from clubs, scenes, commonwealths), staying within the parameters of what constituted a typical performance at the time. There are a few composite characters, and some names as well as some circumstances and settings have been changed to protect people’s privacy. Many conversations reproduced here happen to be word-for-word, often corroborated by other people present at the time or by some other means, but in any case my intention was to get across the meaning of what was said, in context. For the sake of consistency, I kept corrections and additional background or expository information in line with my experience during the period being added to or corrected, and I haven’t amended or updated my opinions or interpretations of events. Though most of the above applies, the first chapter is an exception. It is accurate, at heart, let’s say, and more factual than not, but that chapter is intended to be taken with a shaker of salt (and a pinch over the left shoulder).

That’s a suitable approach to this thing in general. I hope that I’ve characterized the real people in this book as fairly and as fittingly as I meant to, and that pages in here serve as some small tribute to those of them who are longer around. In the end, the goal was nothing more, or less, than a sincere portrait of a rock band. An un-band. Which is like a regular band, mostly.

M.R.

Chateau Marmont, May 2016

1

FALLEN ANGEL

The fetal piglet, eyes shut tight, tongue lolling, was spread-eagled across a bed of wax in the baking tin in front of Pepillo, sliced open from epiglottis to urogenital sinus by a smooth midsagittal cut, and surrounded by a thicket of its own internal organs skewered on steel pins. Pepillo had followed the same instructions, step by step, as everyone else in the class, yet no one else’s piglet ended up giving the impression it had run afoul of a Byzantine warlord. When it came to evisceration Pepillo had real flair.

I grappled with a formaldehyde headache and labeled organs on a mimeographed diagram—fundus . . . spermatic artery . . . pyloric sphincter—while Pepillo, in latex gloves, lab apron, and safety goggles, launched into his new song, accompanying himself on air guitar, imitating. “It goes: Kill your mother, or we will . . . Kill your mother, or we will . . . Kill your mother, or me and Ed will . . .”

Mr. Lee, wearily pacing the aisles between the lab desks, stopped at our pan and looked closer, evaluating. He arched an inquiring eyebrow at Pepillo, who smiled infernally. Mr. Lee moved on.

“You should join our band,” Pepillo said.

“Who’s in it?”

“Me and Ed.”

Pepillo was convincing. As his Andalusian mother told me later, uneasily—Pepillo could sell hielo to Esquimals.

Ed lived in a blue ranch house down the end of the street I lived on, in a leafy neighborhood off the highway. He dressed in denim everything over a black concert tee—his regimentals—and had a massive, headbanger nimbus of wiry black hair that inspired envy and awe everywhere but church and the teachers’ lounge. Ed had been air-drumming since the womb, and air-drumming with drumsticks for better than a year; it was usual for Ed to be twirling a drumstick through his fingers walking the halls between classes at school, eating his lunch, sitting undeterred in detention, and while air-drumming along to Pepillo’s riffing on a physical electric guitar, during band practice, such as it was. Now that Ed had a physical drum set he and Pepillo (who wore his hair neat, feathered, and above the neckline—apart from being teenaged and Mediterranean, his appearance didn’t suggest metalhead) were in business. They called themselves Fallen Angel. “As in Lucifer,” said Pepillo. “The sickest band name ever. Can’t fuckin’ believe it’s not taken.”

We were getting acquainted musically, down in Ed’s basement. Lurching drum crashes, jagged riffing through Peavey Crapmaster amps, feedback squeals, starting and re-starting our way through the list of songs Pepillo and Ed wanted to get together. Metallica, Quiet Riot, Mötley Crüe, Van Halen, requisite Ozzy, Sabbath, the ubiquitous Cinderella ballad. I was on board with most of it, though I was no metalhead. Normally dedication to metal is the principal qualification for metal band membership, more important than �

��pro gear,” “own car,” and other minimum standards I didn’t meet, but Pepillo and Ed were open-minded. And bass players didn’t exactly grow on trees.

Pepillo asked me if I knew “Autumn Leaves.” I’d never heard of it, unless he meant the old standard, by Nat King Cole, or someone, which—since Pepillo was a metalhead—I assumed he did not. (He did.) “That’s okay, we’ll teach it to you,” Pepillo said. He and Ed tried to walk me through the song, all inverted chords and noodly bits and unnatural stretches involving the pinky . . . I didn’t get it. Ed did a counting thing on the hi-hat and said, “See?” I saw nothing. We moved on.

On a break we watched a KISS concert video, an older one, from the late seventies. Gene Simmons’s bass solo involved his bass only in that he pounded it with his fist and drooled fake blood onto it, wagging what people said was a cow’s tongue sewed to his own. I lumped KISS with professional wrestling—fake blood, fake danger—and mostly flipped past them in magazines. Ed liked KISS. Pepillo liked KISS, but was proceeding with caution now that the makeup was off. “KISS coming out [of the makeup, he meant] is like New Coke,” Pepillo said.

Ed, while duly outraged by New Coke, defended new KISS by questioning the infallibility of original, grease-painted space creature KISS. “Yeah, but what about Music from ‘the Elder,’ he said. He referred to a KISS concept album universally acknowledged to be a delusional piece of shit. (I was too young to understand what was going on as I watched my friend’s older brother ritually immolate that LP along with his KISS Army patch and, with trembling lip, unzip his fly and piss on the ashes.) Pepillo shot back the only way any loyal KISS fan could: “Shut the fuck up, Eddie.”

Ed also liked Poison, loved Poison, in fact. Pepillo rolled his eyes. It was complicated business. Metal is all politics and religion.

One evening not long after our initial rehearsal the phone rang. My mother answered. “Why can’t all your friends be more like Pepillo?” she said, handing me the receiver. Pepillo, a matricidal Satanist who happened to have impeccable phone manners, had news: a gig. The date wasn’t far off, so he suggested we move band practice over to his house. His basement rec room would be a step up from the daddy-longlegs-inundated arrangements over at Ed’s. “Plus,” Pepillo said, putting aside his ode to chopping her up, “my mom makes the best fucking torta.”

Pepillo’s mother, petite, and as perfumed and emotional as any Andalusian woman, went to Mass daily. She and Pepillo’s father, a Spanish diplomat of some repute who had little time and even less patience for most things, including the Church, helped Pepillo buy his first guitar on the condition that he commit to the proper study of the instrument. Technical proficiency is primary in heavy metal, and Pepillo had mastery in mind all along; he threw himself into his classical and Flamenco lessons, spending hours in his room surrounded by heavy metal posters of ragged flesh, torture, and madness, dutifully adding deft, liturgical flourishes to the song about killing his mother.

Which is not what his parents had in mind. A week didn’t go by without headline news about some mayhem and brutality wrought by kids under the influence of heavy metal music, a phenomenon warranting lengthy, prime-time investigative news specials with doom-inflected voiceover underpinned with haunted house sound effects; emergency preparedness-and-response handbooks were distributed in “at-risk” communities where hysterical parents scarfed valium, convinced their children could be hocus-pocused into committing suicide and mutilating pets by the likes of Ozzy and AC/DC, or impregnated by a dirtbag under the Dr. Mabuse gaze of Kip Winger. There were deprogramming centers being set up, and work camps employing military will-breaking tactics, with published “success rates.” The stakes were that high. Pepillo’s mother, being a good mother, was on a mission to eradicate metal music from her son’s life before it was too late. And the Flamenco guitar bait-and-switch wasn’t going to cut it.

Mrs. Pepillo sought the counsel of her parish priest down at her church, Our Lady of Perpetual Wailing. The priest came by the house with his maraca of eau de Jesú and shook that around while he said some prayers in Latin to no effect—Iron Maiden still shook the house. She had Pepillo examined by doctors, who found him remarkably healthy, polite, and attentive to hygiene. She had him prayed for by everybody she knew, lit pay candles in every Catholic church in a ten-mile radius, and during a brief crisis of faith purchased from a medium operating from some grotto downtown a highly suspect device purported to detect paranormal intruders, somehow. Whether it was superstition or because it was obviously just a wooden box with a bunch of wires in it that did absolutely nothing, Mrs. Pepillo never used it. Pepillo discovered the contraption in the recycling one day and scavenged it for parts to customize a fuzz pedal.

More than a few times when Pepillo was momentarily absent for whatever reason, Ed and I were interrogated by Mrs. Pepillo; silently catechized over (excellent) tortas at the kitchen table, on our way to or from the bathroom, and on a few occasions in a desperate ambush while Pepillo was still present, which led to heated, rapid-fire Spanish, and Ed and I guessing at appropriate exit cues. Often during run-throughs of Pepillo’s “hit,” we heard Mrs. Pepillo at the top of the basement stairs, hot off an afternoon mass, banging a skillet against the railing in a paroxysm of confusion and heartbreak with the Host still chilly on her tongue. “Pepillo! Pepillo! No me gusta! No me gusta! Basta! Basta!” Once, she pulled me aside and closed my hand around a rank bundle of herbs and asked if I would please hide this somewhere in Pepillo’s room, to protect him. I said I would make sure it got in the room. I handed it off to Pepillo, who shook his head and tossed it in a drawer with the others.

At her wits’ end, Mrs. Pepillo threw up her arms and had her son exorcised. Other concerned parents who feared God, and therefore the demonic overtures of Heavy Metal, had gone this route and according to the latest information, it couldn’t hurt. Pepillo’s account: he sat in a chair as a priest incanted—smack-talked in the name of the Mystery of the Cross. Heed! Be gone! Out, tool of Beelzebub!—and so forth and so on, while bopping Pepillo variously with a crucifix. Pepillo rolled his eyes all the way back in his head until only the whites showed (a talent of his), growled, snarled a few lines from The Omen II, and as the ritual wore on resorted to clearing his throat, looking at his watch, whistling, napping, until finally the exhausted priest admitted defeat. Mrs. Pepillo fell to her knees and wailed like they did in the old country, like they meant it. Pepillo comforted her the best he could, then retired to his room, where he knocked off the rest of his AP calculus take-home (aced as usual), composed a thoughtful, Segovia-like number he called “Satanic Vomit,” wrote the phrase tool of Beelzebub in his lyrics notebook, and went to bed.

Overall the working conditions over at Pepillo’s were good and soon enough we had a set together. A new number, written by Ed, was called “Any Boo Will Do,” “boo” referring to booze. Don’t care if you think I’m lame / cuz I’m drinkin’ Bartles & Jaymes / I’ll be double-fistin’ daiquiris and Purple Passion too / When I take your bittie to the park and chug a Zima while we screw. Short of the masterstroke of “Kill Your Mother (or We Will),” but certainly nothing to sneeze at. As for “Kill Your Mother,” Pepillo and Ed told me, with due ceremony, that they would add my name to the final chorus, so the new last line went: Kill your mother or me an’ Ed and Mikey will. “Shows an increase in power,” Pepillo said. And so it did. Most of the rest of the set list was drawn from songs on the PMRC’s “Filthy Fifteen” list—classics by Def Leppard, Judas Priest, Sheena Easton—and two power ballads, “Fade to Black” by Metallica (we’d open with this, unfortunately) and Bon Jovi’s “Dead or Alive.” Slow songs like this were called power ballads because they had the power to bend the wills of otherwise disinterested women; in this the Bon Jovi song was flat-out sexual sorcery. “There won’t be a dry seat in the house,” said Pepillo, doing his Mephistophelian eyebrows. I doubted even BoJo mojo could redeem us from “Autumn Leaves,” which was also on the list, and sounded like nothing.

We were as ready as we’d ever be for the gig, a Super Bowl party at the DiFazios’ house. Pepillo drove. He’d gotten his license only days prior and was pleased: his driver’s license photo made the Hillside Strangler look like Winnie-the-Pooh. He banged a left at the Stop & Plop and drove us north a few miles toward Watertown, then south a few tax brackets into a realm of guido starter jewelry and shiny Puma track suits called “the Lake,” though there is no body of water there. As it was an Italian-American stronghold, calling it by its official, Native American name, Nonantum, would have been more disorienting.

The males native to the Lake were called mushes. A mush (rhymes with push) tucked his pants into his hi-tops and wore the jacket of his track suit—his guido tuxedo—zipped all the way up, typically under an outsized neck chain, often with a corno amulet hanging on it to keep hexes away from his testicles. Mushes self-identified, and spoke a cryptolanguage exclusive to the Lake called Lakespeak, a mix of Boston English, Gabbagool Italian, and, it’s thought, a lost gypsy dialect. To the unversed average citizen it sounded like brain damage, but in the public school system you picked up basics, such as divia meant “crazy” and “unreasonable”; a jival was a girl, and she was a quistah jival if she was good-looking. Jivals from the Lake were known to empty entire cans of AquaNet into their hair, fusing it into a semitensile helmet that remained inert whether berating a mush or blowing him—or both, Italian chick synchronicity—from the passenger seat of his Cutlass Supreme. Hydrants down the Lake were painted Italian flag colors, and every Elvis Presley Day the neighborhood was a giant block party, an Aloha-suited local police-escorted through the cheering multitudes, whipped up by Holst’s The Planets. Nonantum was Nonotuck for “place of rejoicing.” That might have been overstating it, but a real sense of community down the Lake, whatever else.

Mrs. DiFazio answered the door wearing a sweater with some kind of holiday animal bedazzled onto it, stretched beyond recognition over her breasts, which we knew about anecdotally. She let us in and looked perplexed when we dragged in drums and amps after us.

Adios, Motherfucker

Adios, Motherfucker