- Home

- Michael Ruffino

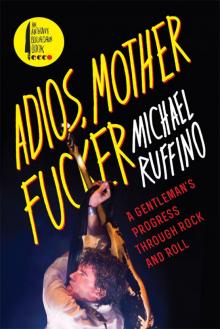

Adios, Motherfucker Page 10

Adios, Motherfucker Read online

Page 10

“The Unband is the stupidest, most depraved act on the scene.”

—NYPress

Lower Manhattan thronged with loud rock bands, boozing it up at all hours. On almost every block below Fourteenth Street, it seemed, there was someplace willing to book even the loudest, most obnoxious of them—repeatedly. A lot of dress-up involved as one has with almost everything in Manhattan, but the atmosphere was promising for us. Matt and I were down in New York often; we got around, met people, and managed to get ourselves a show wherever a greenhorn band could get booked on their wits—scraped together money for promotional handbills and passed them out at every bar we could. All night, every night. Eat at five A.M. three-dollar curry at the cab stand, and repeat. Sunrise, sunset.

Eugene was all for New York so long as he didn’t have to be in the city any more than was absolutely necessary. He was cooking at a decent restaurant, moving up the line, shacked up with Rude Becky (nicknamed by a dementia-wracked former landlord who on one of her anarchic, rent-prising visits mistakenly thought Becky was peeing on the floor when she was in fact cleaning up a spill, as futile as that was). They inhabited a comfortable Northampton existence in clean, spacious digs in the center of town. Rude Becky was from Newton the way you’re supposed to be from Newton, raised to be the sort of person who keeps drawers organized, labels freezer bags, writes things down on a calendar, keeps a checkbook in a particular place, and “balanced” (whatever that means), has multiple sets of bed linens, sends holiday cards, and maintains premium cable without ever having to climb anything holding a pair of wire-strippers in your teeth. You don’t have to know Eugene all that well to recognize that his default monasticism wouldn’t have left him wanting. Couple of jars of peanut butter, loaf of Italian bread, cheapo guitar, skateboard, somewhere reasonably soft to lie down for twelve hours every three days—but he was no fool. When we had gigs he did quick turnarounds, driving down from Northampton with the amps and drums, then jumbled everything back into Rude Becky’s car and got out of the city ASAP, more or less unscathed. We didn’t rehearse much.

One night after playing a sparsely attended show at Coney Island High, a hospitable dump on St. Marks Place, we went up to the office to see the booking agent. This was the part of the night called settlement, where you tried to get the booking agent to settle down, then settled for what they gave you.

“Here you go. One, two, three—four dollars,” the booker said, laying out ones. “And here’s your two drink tickets.”

“There are three of us. And the bar is closed.” We needed gas to get to Massachusetts, more than we needed drinks in New York, incredibly. This booking agent was from Boston; she’d always been friendly, and supportive, gave us gigs all the time, one of the few. We assumed this would be worth something. And so it was:

“Well, I suppose I can give you the cash equivalent for the drink tickets.”

“And how much is that?”

“Six dollars.” She broke the uncomfortable silence. “I guess I can do seven.”

We loaded the equipment out into Rude Becky’s car; she leaned on the horn, yelling for Eugene to “move his stinky ass” (she embraced her nickname). Eug got in and they peeled off northbound.

Matt and I stood on St. Marks at 2:22 A.M. The night’s take combined with all of our personal monies, we had eleven dollars between us. After splitting a falafel, in order to think, we had seven. Not enough gas to get much past Yonkers, in my heap (a ’92 Ford Anonymous, my beloved Buick long gone). We went to a place called Marz Bar, that festered like an inoperable wound on First Street, where our money would get us much further.

Couch-surfed around the Lower East Side, slept in the park a couple of times. Getting home was the directive, but not the priority, and days and nights cycled too quickly to get a handle on anything. We kept an eye on the parking signs and moved the car accordingly. This sometimes meant waking up and double-parking on the opposite side of the street and sleeping half-shitfaced in the driver’s seat until the tow danger was past. Street cleaning hours roughly coincided with when the Dominicans in the neighborhood understood it was time to wake up and go to their windows and begin shouting continuously, so we rarely overslept. When the tank was too low on fumes to start the car, it settled down the end of Attorney Street. For weeks it was cannonaded with tickets, then stripped, booted, and finally towed away, into some other dimension, for all we could do about it. Thus it happened that Matt and I were relocated to Manhattan, sans fixed address. Sooner or later you did have to be in New York.

So began the time of perambulation with toothbrush and sunglasses.

One night some months on I was ricocheting around on diet pills at a club up in the Twenties, no idea what I was doing at a jam band event, people twirling, and I met Erin, a music publicist and dominatrix. Not necessarily in that order, either way in the humiliation business, doling it out or reeling it in. She sounded like she knew what she was talking about. She was managing an almost almost-famous band on the side, called Jonathan Fire*Eater, and I decided that she ought to manage our band as well. I’m not sure now how I worded that to her. Somebody ought to do something about us, in some capacity, soon, that was the gist. I remember not quite understanding why her response included a punch to my solar plexus. As a rock and roll professional she had what you called “chops.” That was clear enough.

Erin knew her way around and she worked quickly. We played better shows more frequently. We were written up in the papers more often, in articles that sometimes mentioned we played music. Much of our earlier press in New York gave the impression that “The Unband” was a nihilist art unit formed to swindle females, ruin book parties, and trigger alcoholic relapses—an Alphabet City boogyman, not a musical group. (You couldn’t swing a six-pack on the Lower East side without hitting an indie journalist in recovery, a potential relapse around every corner, in a community you couldn’t walk half a block without being offered some kind of drug, where even the nursery-chiming Hoodsie truck sold dope, they had to be vigilant.) Erin took us up to Chelsea to meet John “Beaver” Truax, a connoisseur. Lean, eminently sociable in wire-rimmed specs and boat shoes, maybe forty, maybe older, or younger, Beaver presided half-dancing with a joint in his mouth over a continual dinner party in the Chelsea loft he’d built by hand. You’d be there talking with a famous Jamaican reggae producer who just popped by, I and I stoned out of I and I’s and everybody’s mind, and Beaver would slide up and fill your glass with Claret from a hand-numbered bottle and hand you a piece of cheese made from baby unicorn milk, then someone else operating at or around the peak of whatever business he or she happened to be in would drop by, more wine, more everything, and at four, five in the morning Beaver would throw on some rare, mind-bending, deep-funk record from his wall of expertly collected LPs, shimmy around in front of his stove for a couple minutes, then toss a Michelin-level bowl of shellfish onto the table in front of you, point at it, and say: “Dude. Clams.” Beaver came to see us play one night, got a good laugh, and was inspired enough to use his myriad connections to try and connect us, a co-manager. And I moved into his spare room.

Pretty quickly, through Beaver, we had a “demo” deal, granting us a small budget to record a few songs on spec for a new mega-label formed by David Geffen, Steven Spielberg, and movie executive Jeffery Katzenberg, combining like Voltron. Then came the recording session with the hotshit producer (Daniel Rey, who’d recorded the Ramones, Raging Slab, Gang Green . . . ) on the grail-like recording console (Neve) some classic album (Bowie?) was mixed on . . . Near deals came and went but any disappointment was short-lived; prospects were good, hopes high. There was plenty of day drinking, couch- and bed-hopping, and emerging from druggy basements into despotic sunlight to marvel and tsk at the commuter class. I don’t know who was driving whose car, speeding us through the predawn streets, a one-car Manhattan Grand Prix, when we swerved onto a freakishly empty Fifth Avenue and all the traffic lights went green. Whoever was driving floored it: 40 . . . 50 . . .

60 mph . . . I was up there, spread across the roof with my fingers dug into door trim on both sides, wind pounding my eardrums, in the right place at the right time.

Max Fish was a bar on Ludlow Street. It was Erin’s local, and once she introduced us around the fact that the overhead lights were kept on all the time ceased to be a problem, and we’d be there most nights, sitting with Carlo, the Fish’s social director, who administered a sort of depraved Algonquin salon crammed into the front window nook. Writers, painters, filmmakers, actors, performance artists, graffiti artists, cartoonists, local bands, foreign bands, and alien ones, all pig-piled around an undersized table hidden by a morass of highballs and shot glasses. You could miss an entire art movement if you went for a piss—as New York City is supposed to be. Many things to many people, the Fish wasn’t a live music place for anybody, but Miss Management, as Erin had dubbed herself, arranged with the owners, Ullie and Harry, that we could play a show in the back. Apart from my kneecapping Wilma, a friend of Erin’s from the S&M circuit, and nasty looks from one or two people I grabbed drinks from who actually minded, the show went off without a hitch. Someone else relieved us of having to move the pool table back in from the Pink Pony cafe next door, and a guy named Dave pinned us down at the bar and started talking to us about a recording contract. He was from New Jersey and incongruous to the music industry as we knew it. Which was maybe a good thing.

After we’d wrapped up with Dave, Lord Riley walked in the door. Lord Riley, who once told me I was what pink elephants saw when they were drunk, was down on the commodities exchange now, trading copper, or hogs, or something. He sat down next to Matt, and made some uncharacteristically polite small talk that worried everyone, and then—sure enough—blasted Matt, point blank, with cop mace, and walked out the door. Lord Riley was busy downtown. His visits tended to be brief, and memorable. A droog version of “Be Here Now.”

Jersey Dave turned out to be all right, and a few weeks later, after some minor negotiation, we agreed to sign a contract with the small—tiny—independent label he worked for, called Payola.

We signed the paperwork at the Payola office, a congested salaryman’s nest in an old deco building up on Madison Avenue. Everywhere there were precarious stacks of CDs, music magazines, padded mailers. We had a celebratory beer with Jersey Dave and the CEO of the label, Clem, who was rumply, and a little out of his depth maybe, but we wouldn’t be dealing with him much, and not on anything creative. The only other employee was the newly hired receptionist. Merinda, from Long Island. You could be forgiven for thinking Merinda was born in a shopping mall but she was sharp, easily the sharpest tool in the Payola shed. Luckily selling bands isn’t rocket surgery.

Our deal alloted us a few thousand dollars for recording, mixing, mastering, and packaging, and little to no tour support, we’d be mostly out-of-pocket on the road. There was no advance, just a few hundred for equipment repair, strings, basics we lacked. Instead of the proposed recording situation in the city we opted to record back in Western Mass at Slaughterhouse, with Mark Miller and on Payola’s insistence another engineer, John Smith, who’d just done a Ramones album. We recorded a dozen or so songs in a weeklong blitzkrieg of vicious all-nighters, all particulars and incidentals jubilantly, proudly underwritten by Ivan, who also provided the down payment for the session, when Payola’s check failed to appear as promised.

The last day of the session Jersey Dave came up from New York on the train, with a check. He wanted us to record a cover song before we wrapped. He and Clem agreed that a timely cover song would be a good investment. We did an utterly unconsidered take of “Everybody Wants You” by Billy Squire. Dave, nonplussed, asked if maybe there was something else we felt like recording. There wasn’t. He didn’t seem to be one hundred percent sure of our album title, either. We’d chosen that on day one: Retarder, a word printed on the manufacturer’s tag of the studio sound baffles, the portable walls used to isolate instruments, called sound retarders. Seemed apt.

As the album release date approached communications with the label went dark. We couldn’t reach Jersey Dave anywhere. With Merinda’s help we nailed down a meeting with the label (cupping the phone, “Should I keep telling them you’re not here, or have you grown a pair?”). Erin was over in London shooting a pornographic music video with a band called Ash, and Beaver’s role as a well-connected idea man didn’t include talking to no-idea men like Clem, and anyway he’d just received an unexpected delivery, a whole, live, sawfish or something, so Matt and I went to New York to get to the bottom of things.

Clem greeted us. He was alone in the office. We sat down at the conference table. Clem said, “First of all, love the record. Really great, really, just . . . great. Really great. So, now—what is this I’m looking at here, exactly? This is . . . what?” Our mock-up of the CD cover was spread out between us.

“That’s the cover.”

“Mmn-hm. Yeah, okay, well, we’re feeling that we feel this doesn’t work as a cover. Our feeling is that it doesn’t make any sense. I mean, what’s the message, what are we saying here, with this.”

“Message?”

“Yes, message.”

“It’s a girl in a bikini holding a hot dog. What message.”

“Come on, guys. What do you think of when you see a hot dog?”

“Food.”

“Pigs, distantly. What do you think of?”

“Well, it’s a penis,” said Clem. “I mean, I’m saying someone could see it that way. Like she’s about to commit fellatio.”

“Commit fellatio?”

“You know what I mean. Do fellatio.”

“The hot dog’s in a bun. And it’s got condiments on it. It’s obviously food.”

“It suggests a penis.”

“You suggest a penis.”

“I just call ’em like I see ’em,” said Clem. No one was arguing with that. “Also the title doesn’t work. We feel people might get the wrong impression about this girl. That this girl is retarded.”

“I don’t think we’re using that word anymore, in the way you’re using it.”

“Well. People still think it.”

“Fair enough. So, is the problem that someone might think this woman has cognitive issues, or think that we’re suggesting she does, when she doesn’t?”

“The problem is we have to be sensitive to people who are differently . . . mentally abled.”

Matt glazed over. I said, “The album title is Retarder, not retarded.”

“Same thing.”

“Not at all.”

“Oh really,” said Clem, condescending. “How is it different?”

“They’re spelled differently and refer to completely different concepts.”

Clem frowned. “This isn’t English class.”

“That’s the first rational thing you’ve said,” said Matt.

“Okay, listen, guys, here’s the deal—”

“Where’s Dave?”

Clem rubbed his watch. “Dave’s not coming. So. Bottom line, I’m not releasing this album as it stands.”

“Come again?”

“Who are you? Aren’t you the accountant or something?” Matt wanted to know.

“I’m in charge is who I am, and I’m very serious.”

“Where’s Dave?”

“Forget Dave! Dave’s not in this. Geez!”

“Okay, then,” said Matt. “So we’re at a stalemate.”

“Oh no we’re not. That’s not how this works.” A rat sprang from somewhere and dashed across the table. Clem snatched it up and slammed his teeth into its neck, drained its vital fluids in one, slobbering suck, then hucked the bloodless, twitching carcass at the wall, where it left a trail of gore as it slid down into a wastebin full of demo CDs.

“See, legally,” Clem said, producing a handkerchief and dabbing the corners of his mouth, “I can release this album any way I want. I can put any cover I want on here. My face, whatever I want. That’s a fact. I’m willing to give you guys the op

portunity for some input. Because I’m a nice guy. Just remember, I don’t need to, legally.”

I imagined Clem’s face, which fell aesthetically somewhere between a slapped-ass and a rotten Jack-o’-lantern, in close up, as our cover, with the current title. It was good.

Clem changed tack. “Okay. How about this. How attached are you guys to your name? The album title might work if we change the band name.”

“It’s been ten years,” I said. “What do you mean ‘how attached are we’?”

“Well. One or the other.” Clem sat back, interlocked his hands behind his head. He had the physique of a wet donut. “You want that cover, we change the band name, or the album title.”

“Out of curiosity, what would you change the band name to?” Matt said.

“Good question!” Clem shot forward. “That’s the fun part! We’ll come up with one together! Right now! We’ll do it this way—I suggest a name, then you guys suggest one, then I’ll suggest another one—back and forth like that.” He slammed his palm on the table. “Bam! See? That’s how it happens.”

“How what happens?”

“Back and Forth. See that? It’s perfect, because there are two of you.” He matched his index fingers and thumbs and pointed to us individually. “Back. And Forth.”

Matt said, “Wait. I missed it. Which one of us is back and which one of us is forth.”

“Doesn’t matter.”

“Ah, I don’t know about that,” Matt said. “Seems pretty important.”

“Up to you, then. I’m just tossing out ideas.” I reminded Clem there were three of us. “Okay. Well . . . it still works,” he said; he kept to himself how.

“To and Fro,” Matt said.

“What?” said Clem.

“To and Fro. Instead of Back and Forth.”

“Yes! Even better! Okay, now we’re getting somewhere! See? Now you’re thinking! See! This is, like, how it happens! This is rock and roll, guys!” said Clem, possibly manic.

“Let me get this straight,” Matt said. “You would be okay with releasing this album, as is, and calling it Retarder if the band was called To and Fro.”

Adios, Motherfucker

Adios, Motherfucker