- Home

- Michael Ruffino

Adios, Motherfucker Page 2

Adios, Motherfucker Read online

Page 2

The DiFazios’ split-level was a cut above the three-decker dumps around it. Even the bathroom had wall-to-wall carpet, top-end lino in the kitchen, dimmers on every light switch—Mr. DiFazio’s contracting business was doing all right. The DiFazio sons, Tony Jr. and Tony Jr. II, were like mush princes. They kept up their grades and were athletic stars with their choice of baseball scholarships, but they weren’t high and mighty about it. They let you know they tucked their pants into their socks one leg at a time like anybody else.

The pregame was on a Magnavox projection in the paneled family room. We set up our gear behind the couch, as out of the way as a metal band can be in a private home not expecting one. Mrs. DiFazio served manicotti and tended to the sideboard buffet of game day dips and skewers. We plugged things in and tried to figure out why they didn’t work while Tony Jr. tried to explain us to his father.

“What fuckin’ band. It’s fahkin Supabowl, what’s wrong with you,” Mr. DiFazio was saying.

Tony Jr. said, “What. For halftime, Pa.”

“What if I wanna watch the halftime. You think about that?”

“I’m just saying. There’s a band here.”

“I can see that. Why is there a band here.”

I went out the door into the carport for a smoke with Ed. Neither of us knew how to smoke, but we had cigarettes and the notion that this is what you did. Pepillo came out with the set list, which under the circumstances needed adjusting. Not the debut gig we had in mind. But what band’s was? None, probably. Probably Van Halen’s first gig was a lot like this.

We played during the commercials, except during the overhyped new M&M’s ad (everyone was disappointed), and not during the Madonna one, which the younger Tonys wanted to see, Madonna shake her quistah quivals (breasts). When the halftime show came on we took a break and sat on our amps eating Mrs. DiFazio’s manicotti and snacks.

On the television the announcer introduced the halftime show—“Live from Pasadena, California, land of make-believe!”—followed by a confusing graphic about Hollywood.

“What is this,” said Tony Sr., tipping his Genesee, a cream ale, toward the television.

“Halftime, Pa,” Tony Jr. II said, around a manicotti tube.

“I know that. I’m sayin’ what ah they doin’.”

Tony Sr. watched men wearing glittery white cowboy costumes and fake mustaches leap like lords, twirling all over the gridiron to the theme from Rawhide.

“Jesus and all the fuckin’ disciples what is this,” said Tony Sr.

“I dunno, Pa. Up with People or something, they said.”

“Up what with which people?” Tony Sr. said, as the Disney chipmunks pranced onto the field in twee cowboy vests and assless chaps to a tarted-up version of “Footloose.” They locked elbows, and, luminescent with rhinestones and metaphor, skipped toward the End Zone. “Mother ah God,” said Tony Sr. “Mona! Get in heah!”

“Whoa,” said Tony Jr. as Sheriff Goofy appeared on screen, clapping in time as a cowboy in extraordinarily high spirits behind him pretended to ride an invisible horse, though that wouldn’t be the first thing you thought of. Tony Jr. chucked a throwpillow at his brother. “You know you got a wicked woody right now, mush.” Tony, Jr. II whipped the pillow back. “Coo-ya moy! Fahkin’ chooch.” He sprang onto his brother and viciously charliehorsed him; Lakespeak used the same punctuation as regular-speak.

Tony Sr. sprang a finger from his beer can, jabbed it at the TV. “Look at this! Mona! Look!”

“What, Tony. I’m looking,” said Mrs. DiFazio.

“First your cousin, now this. Look at ’em! Now they got football.”

“Don’t be ridiculous.”

“Who’s bein’ ridiculous. Look at ’em. Look! Look at that!” The image on the expansive projection screen cut to the blimp-cam high above the gridiron, as the performers pranced together forming a humongous, twinkly, glittery, anti-Reagan dodecahedron that undulated kaleidoscopically to “Flashdance (What A Feeling).” Tony Sr. watched it shapeshift. Adapt.

“Holy Jesus. Holy . . . See? This is exactly what the Russians are waitin’ foah,” Tony Sr. said. “The Chinese.”

“Cahm ya horses, Anthony,” Mrs. DiFazio said, re-upping everyone’s manicotti. “They’re just Broadway people dancing.”

“Hell they are,” said Tony Sr. “That’s Dukakis’s ahmy right theah, he gets his way. He gets in the White House, mahk my werds, we’re sittin’ ducks. One day—boom! and we’re waitin’ in line ta take it up the—”

“Oh fachrissake, Tony! That’s crazy,” said Mrs. DiFazio, circling the room with the hors d’oeuvres plate. “Dukakis couldn’t get in the White House with a gawddamn tooah groop.”

“You don’t know that, nobody knows that,” Tony Sr. said. “They can do subliminals now. On ya mind.” On the television showbiz cowboys danced an interpretive hoedown, swinging bullwhips. “The powah of suggestion,” said Tony Sr., quietly.

“Nah. That’s just in the movies, Pa,” said Tony Jr.

“Oh no, smart guy. They can do ’em in TVs, magazines, everywhere,” Tony Sr. said. “Who knows,” he added, returning a pig-in-a-blanket to its decorative platter.

The halftime show was ramping up to a finale. Batons twirled and brass crescendoed as drum lines curlicued and the Disney mascots broke out of their conga line and paired off. Whatever they made-believe out there in Pasadena, California, anyone in the Greater Boston area, regardless of social viewpoint, would recognize what Goofy and those chipmunks did next as humping. The cowboys and cowgirls were going at it, too, all over the field, with whips and ropes—Disney goes Gomorrah. Tony Sr. appeared to be levitating.

Pepillo, reading the room, flicked on his Crapmaster Pro and amid the squealing torrents of feedback launched, “Kill Your Mother (or We Will).”

Reception was mixed. The young Tonys grinned, headbanging. Mr. DiFazio remained motionless as his face cycled through colors like a malfunctioning chameleon. Mrs. DiFazio stood there holding the drooping foil tray of manicotti and gave us a hard look. A look Pepillo had no trouble reading, and had prepared for. He gave Ed and me the hand signal that meant: after the guitar solo, go straight into the Bon Jovi ballad.

2

THE CONNECTION

In the standard hirerarchy of rock star archetypes The Bassist is subordinate to The Guitar Hero, The Messianic Singer, and The Madcap Drummer, above only The Keyboard Player and, usually but not always, The Oversexed Roadie. Which is why in the average high school music scene there wasn’t much competition for the bass playing job. If you could play two notes in succession on the same day on a bass, there was a band who’d have you, and if you could do any better than that, the challenge was saying “no,” before you found yourself spread too thin.

I played bass in five, six, bands, regularly. One covered Chuck Berry, the Beatles, the Kinks, plus “Good Lovin’,” “Dock of the Bay,” and so forth, all wholesomely enough to play school dances; another played Bachman Turner Overdrive and Stevie Wonder, with a drummer who rendered them all but indistinguishable. The Rush—Pink Floyd—Yes “experience” (no name, just a symbol, like an ankh, but more . . . whatever) had two drummers, one of whom used a drum pad to control a laser light show he built from scratch while I controlled huge, byzantine synthesizers with a modified set of Taurus foot pedals, which seemed like a good idea at the time. There was Wellbaby OK (as in the infant has been safely extracted from the waterhole), fronted by my friend and, according to a letter sent by the school to a couple of dozen parents, “co-conspirator,” Gabe. Gabe had what a gearhead supporter of ours called “wicked pissa choral skills, but not in a gay way,” in other words, in addition to anthemic punk we could pull off deep cuts from Tommy that tanked at dances—the crowd wanting “Kokomo” and “Hungry Eyes” got a twelve-minute version of “See Me, Feel Me” straight into the Misfit’s “I Want Your Skulls.” There was the project with Kaspar, an orphaned music prodigy temporarily living at our house. (Not the first or the last troubled c

lassmate to move in with us—my parents were consummate Samaritans.) Kaspar played an electric violin that looked like a weapon designed to kill Picasso, drove a brand-new BMW, and had a functioning credit card not in his name. A couple times a week he drove us—at two hundred miles an hour, Bauhaus whumping from the Blaupunkt—out to an industrial park somewhere in Medford, where we would record horrible, irritating noises for a shock-haired Belgian wacko who said he was a neurologist interested in testing “highly stressful frequencies” on people strapped to chairs with electrodes on their head. I’m not sure that counts as a band.

I also had the odd, paid, solo gig on the session circuit I’d stumbled onto, after agreeing to be in the pit orchestra of the school musical because there was an interesting woman in the cast. You can’t unsee someone participating in a musical, I learned, but, as that shut a door on a romantic pursuit (dead-bolted it) it opened a window. I got calls to play in pit orchestras in other towns, one gig leading to the next by word of mouth. A church production of The Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat in Copley Square was interminable; at times nightmarish, and nearly drained me of the will to live, but I got three hundred dollars to basically sleepwalk through it; that begat a gig with a community theater group out in Randolph bumbling through Cats (landing on everything but its feet), where I got two-fifty cash, plus all the honey-ham sandwiches and Nescafé I could swallow to endure a long weekend of jazz hands and Prozac stares that made your blood run cold.

It was all slight variations on flimsy ham sandwiches, kick lines and choruses of Lithium-chomping theater people, and degrees of the guy next to you holding a guitar and a grudge against the world, perpetually up to the eyeballs in payments on the pseudo-sports-car (yellow, often) he “cruises chicks” up in Revere beach every weekend, cranking neo-be-bop and inadvertently deselecting himself from the gene pool every way possible, for which we can be thankful. Maybe a perfectly nice guy if you get to know him, certainly a taxing hang meantime, while he’s there quizzing you on aspects of guitar theory, and providing unsolicited advice about “babes” though he doesn’t seem to know any.

The apex of the session biz was jingle money. You heard big fish stories about just how good it could get. Tales of the Jordan’s Furniture theme song composer buzzing around Nantucket in his hovercraft, swimsuit models hanging all over some Bono of supermarket ditties. Kings of the earworms—tunes so catchy they seem to tunnel into your brain and burrow too deep to dislodge with less than a shotgun blast. I didn’t want that blood on my hovercraft.

On the other hand, there is a definite advantage to assuming the position of a working instrumentalist, mainly because you improve your chances for free travel, I knew. When I learned—through Gabe, conspiring—that the school choir, on the eve of a three-city tour of Canada, lost their glockenspielist (Melancholia? Dropsy? Glockenspiel malfunction? Who knew how a glockenspielist was lost, or what one was) I went and found Mrs. Taylor, the choir director. She was in the music room, swooning, the back of one hand glued by despair to her forehead, the other steadying her costume wig. She got “the vapors” like this when she got a parking ticket, or stepped in a puddle—all crises had the same, unbearable, weight. I told her I could play the thing, the glockawhatever, and would be happy to fill in. I figured it was a horn or something, and I could get notes out of a trumpet well enough. Forty-eight hours later I was in front of a full house onstage in a Toronto music hall, whacked out of my skull on Alaskan Thunderstick, holding a bound score I could only maybe read some of, waiting for everyone in the orchestra to take their positions, on the principle that whatever instrument wasn’t taken would be the thing I was supposed to play. Glockenspiel. Not a horn, it’s like a xylophone. Close enough.

All of that felt about right. At three that morning (or was it the next?) I was drunk under a pool table somewhere in a foreign country, latitude and longitude unknown. Didn’t matter that it was only Canada, and I probably could have walked home if it came to it. I felt some deep machinery locking into place; armed and engined, as Kipling said, about something else.

I was out on the bleachers in the lacrosse fields, riveted to the latest edition of the CVS prescription drug guide, and a punk girl I knew came and sat down. We were talking about music and bands, ones we knew. She said, as she had in the past, sensibly, that playing in a zillion bands wasn’t going to get me anywhere, and that I ought to meet her friend Matt. Matt played guitar in a punk band called Afghanistan Spoon Festival, a phenomenon from monolithic North High, across town. I’d seen their handmade shirts around, the lopsided logo on the front and their slogan on the back: EAT CHEAP FOOD, BUY CHEAP CLOTHES, PARTY WITH NO MONEY. LIFE WITH ASF. That was enough to get me to one of their shows, in a lobby at Brandeis University—I couldn’t get in, it was beyond sold out, a pile of humanity, bodies airborne. The punk chick, who I liked but had a lip stud that always made me want to hand her a napkin, said ASF had just broken up, mainly because her friend Matt decided he’d taken it as far as it needed to go, to that effect. An unusually wise move. She didn’t have his number offhand, but said he worked at the Coffee Connection, a coffee shop not far from my house. A few days later I walked down there to introduce myself.

This was Newton, “the Garden City,” a few miles west of Boston. It was divided into thirteen neighborhoods, called villages, ranging econmically from Chestnut Hill, its Beverly Hills, with outsized homes, lush streets, twinkly shopping areas, to others closer to the Charles River—the Lake was one—where you found the three-decker homes with minimal yards more typical to Boston’s urban areas. There wasn’t any wrong side of the proverbial tracks in Newton, mostly there was a whole lot of middle. Newton had the highest-rated school system in the country, according to certain people who rated things, which is why my family moved there, from Hingham, a small town about forty miles to the south, near Cape Cod, on what is known as The Irish Riviera. With the Cape as a human arm flexing its bicep, the Irish Riviera is a string of shore towns that runs along the deltoid, Hingham at the bottom edge of the trapezius.

When you told a kid from a place not known for rampant solvency, like Southie (South Boston) or Eastie (East Boston), that you were from Hingham, that was plenty for him to go, “So, what. You think you’re better than me?” or more succinctly, “Well! La-di-da!,” galled by the idea that you wiped your ass with handtowels, and would do the same with his father’s paycheck if it were handier. The most egregious offense to Bostonian mores is putting on airs—acting above your station, and by living in places like Hingham you were guilty of this until proven innocent, to the extent that you could be. Your family’s financial reality and actual social standing were irrelevant. Newton was affluent, too, and was known even in Hingham as “Snooton.” Also, “Jewton,” because around thirty percent of Newton’s population was Jewish. Few kids on the uniformly gentile Riviera knew what a Jew was, beyond a type of kid enviable for his eight Christmas mornings, to our lousy one. La-di-da.

As if in the Boston area a coffee shop other than Dunkin’ Donuts wasn’t already dubious—this Coffee Connection, in Newton Center, was like a shadowy recess in a bazaar in Eritrea; a beatnik hovel smoldering with foreign aromas, the sidewalk out front crowded around the clock with musicians, painters, undeclared artists, and professional degenerates, vibrating on African rocket fuel, shoving handbills and bad poetry and demo tapes at each other and at commuters exiting the T stop across the street who failed to pick up their pace.

Toxic Bill was there, as usual, and as usual, he had a new demo tape. His metal-punk crossover band, Toxic Narcotic was insanely prolific, and there wasn’t a telephone pole in town that didn’t have a gruesome T.N. flyer on it. His new tape was called Wunt Dunt Dunt, onomatopoetic for the sound of the quintessential thrash metal riff. Toxic Bill was burnt out nonpareil and had what you’d have to call a goatee, since there’s no name that I know of for a misshapen Hitler mustache on your Adam’s apple. He popped the tape into a Walkman and snapped the headphones on my head to play me “Silen

ce Equals Death So Shut Up and Die.” A new high and low, simultaneously.

Inside, amid the clutter of postcards of perturbed-looking llamas and sun-caked indigenous peoples sent by former baristas on spirit quest leave, I introduced myself to Matt, the Connection’s lone non-hippie employee. Matt was slim, pale, mild-mannered, and a few years older than me. We drank coffee, talked a bit. He’d renewed his driver’s license that morning, in the Butthole Surfers T-shirt he was wearing; his grinning photo cut off just below “Butthole.” We got along, and made a plan to play some music at my house, which seemed to me would have happened even if I had met Matt for some other reason.

We lived in a seventeenth-century saltbox, one of the oldest houses in town. Empty of furniture it was like a house you’d see in a reenactment village, an actor in garters hanging around pretending he didn’t know what a television was. At the open house the realtor said Edgar Allan Poe had once lived up on the third floor. She said she didn’t know which room, even though as she spoke only one of the rooms had a freakish crow on its gable, staring at us. The house sat ten feet from the highway on-ramp, which meant the price was right.

I had a little musical setup in a corner of the basement, a dirt floor with colonial artifacts strewn everywhere; fossilized nails, tool handles, crock shards; we learned it was likely a station on the Underground Railroad after a cable guy fed a hundred feet of coaxial wire into a walled-off room behind the root cellar. Matt came over one night with an acoustic guitar, an old family heirloom, and a bulky cassette machine, “Property of Newton North High School” singed into it. We recorded a song, very ponderous, about whether a man’s head weighed more when his thoughts were heavy. We called it “Weigh Your Head.” The recording ends abruptly with the voice of my father, scolding us from the top of the basement stairs, saying, “This is bad stuff. A very dangerous road you’re on here. Very dangerous.” Nothing to do with the music, which he generally supported. He meant staying up late, which could screw you up “worse than any drug,” he said. My father was under a lot of pressure at the time. He was about to enter the priesthood in the Episcopal Church, which at some point would involve a ritual called the “imposition of hands.” Probably not as bad as it sounded, but a phrase that might lead to some experience with losing sleep, if not full-bore panic attacks.

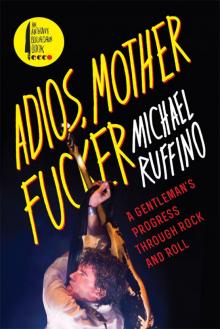

Adios, Motherfucker

Adios, Motherfucker