- Home

- Michael Ruffino

Adios, Motherfucker Page 4

Adios, Motherfucker Read online

Page 4

Around the corner from my apartment, across Harvard Avenue from the packie mothership where everybody knew your name, but not necessarily your age, was a nefarious hole called Bunratty’s, a cornerstone of the scene, rumored to be crumbling under piles of violations. The English guy who booked there, surnamed Crapper (he told us, wearily, no, he was not related to the inventor of the toilet, whose name wasn’t Crapper) encouraged us. He suggested we’d do better in London, as if that mattered, and meantime gave us increasingly good slots and paid us well, when few places would. The scene was in flux; the emerging aesthetic wasn’t for us, and if anyplace was holding the line, it was Bun’s. Good nights there often felt like a habitat in need of preservation.

As a regional aesthetic New England rock is nothing special. A “little arty,” indicated by a quick wag of the flattened hand, palm down, is fine, but there is no local impetus to re-invent the wheel, nor much patience for anyone who thinks he can do so. The native sound, such as it is one, is mainly a smartass interpretation of an existing style. The Remains did smartass Stones opening for the Beatles in ’66, later The Modern Lovers’ smartass Velvets, DMZ’s smartassier Standells. Nervous Eaters, The Bags, Lyres, more recently The Flies, The Clamdiggers, The Titanics, local paragons of smartass all.

Pixies (“little arty”) were the last Big Thing, and a couple of female-fronted bands were lately marked as next Big Things, drawing national attention. Sightings of record label scouts around town had bands scrambling to replace unattractive band members, write bigger choruses, revamp personal definitions of “selling out,” and the next Big Thing status seemed likely to go to one of the many bands doing for beta maleness and clinical depression what Ted Nugent did for gibbering yahooism and bowhunting. They tsked you backstage for changing clothes before you went on, and on stage they stared at the floor and moped, like their moms had forced them up there, straight from bed. If you were lucky they threw a tantrum, or keeled over from acute ennui. Then someone next to you would go, “Whoa. They’re gonna be huge.”

Our new cassette, called Sink, was close to semi-professional almost. It got us a few gigs, but not many. Fellow musicians told us the reason we weren’t getting traction on local stages, apart from duct-taped Chelsea boots, was that we didn’t take ourselves seriously, equating that with projecting seriousness, instead of actual resolve. Nothing could be done with that. Pretending, never mind believing, that your music was serious, like soldiering or heart surgery, made you look like an ass now, and a joke later. And if playing a show in a gorilla mask and swim fins implied a lack of dedication to anyone, they ought to try it.

Not that we were outlandish by design. Bands like Space Humpin’ $19.99 and the Pajama Slave Dancers more ably covered that territory. On top of the usual guitar and amp smashing, we might do a skit or sock puppetry, Eug might don his birthday suit. Mink had an intoxication threshold—and Mink could consume an out-of-reach White Russian remotely, by twiddling his multi-ringed fingers at it—beyond which he past-life regressed to a polar bear, to where you feared the seals over at the aquarium might be in danger. We had variables, is all.

We got into trouble at one club when somebody we knew threw a dead rat onto the stage. We began playing a song called “Dead Mouse,” which, in retrospect probably made the act appear staged, though it was not. One of us kicked the rat, it took a funny turn or two, maybe hit some things, maybe beaned somebody’s girlfriend, who happened to be an animal rights crazy, etcetera and so on, very unfortunate. Or, for example, I was getting offstage somewhere or other and right away here’s a soundguy in my face going on about my having to “pay for the monitor I blew up.” I laugh in his face, of course, because the four packs of Marlboro reds I smoke every day says I couldn’t blow up a paper bag enough to pop it, let alone inflate some fancy eco-monitor, or whatever. He reacts by calling me “unprofessional,” implying he’s in a position to decide, i.e., he puts on airs—now we have a problem.

In fact that simple misunderstanding happened because I engaged before I had properly decompressed after that show, poorly attended as it was. The process I refer to isn’t really decompression, not the way a deep-sea dive requires, just loosely analagous.

Assuming you go all-out when you get on stage, the first few minutes after you get off, so to speak, can be tricky. Bright lights and extreme decibels can leave you with flash blindness, distorted vision, equilibrium problems, temporary deafness, or all of the above. Always there is the scree of tinnitus, which can be distracting, if not outright disorienting (one day that will be permanent, but not today), and when the epinephrine flow, the fight-or-flight juice, cuts off as if by spigot—it’s all downhill from there, fast. You might find your basic motor skills are unavailable. Speech can be reduced to palsied barks, says into a soundguy’s face, as above. In the extreme case, which is usual, all five senses melt into one, antediluvian, monosense. Drooling is not unusual. You are incapable of distinguishing war and peace, shit and Shinola, friend and foe; you have the response spectrum of a stroke victim, or a hyperevolved houseplant—You might crane toward water, if anyone around ever had any that wasn’t actually vodka. Frequently, this is the condition you are in when you get offstage and someone comes and says, Good show! or Get out of my club forever! or Fuck You, I’m pregnant! while you stand there trying to figure out how the hell your thing (guitar) fits into its fuckwhat (case).

Most of the time the worst that happens is semantic, accidentally insulting someone, or appearing to be intellectually disabled. One night, after a Bunratty’s show, we almost lost Eugene because of it.

Crimes, a friend of Mink’s, lived in a basement apartment around the corner from the Buns, close enough to be a dressing room when we had a show there. Crimes was all right. People we knew sometimes said he wasn’t, and the Commonwealth had an ongoing interest in proving he wasn’t, and, true, his friends and associates—Satan, Death, Drugs, Stabby, Psycho-whomever—swapped techniques for breaking someone’s jaw on a curb like a Hun sewing circle, but Crimes was good enough to cover his tarantula tank with a blanket when I was around, after I told him I had that phobia.

Eug, Mink, and I were over there once, straight from the stage at Buns, to decompress. Matt was at the club with his parents, who’d come to the show, where an arty trio called Morphine, a sax-bass-drum outfit, was playing their debut gig, getting the “Freebird” treatment from B.U. mooks. Crimes let us in, then snatched up his keys, transferred the six-foot boa constrictor from his collar to Eugene’s, and said, “Watch my snake.” Then he flew out the door and up the stairs to the street.

Warbling on the TV was a bootleg concert video, Jimmy Page, of Led Zeppelin, with his new band. The band sounded a bit like Whitesnake, a hair metal band whose success was based on not quite violating Led Zeppelin copyrights. Hair metal bands like Whitesnake had overnight become non grata. This transitional period in Boston was merely a reflection of a national trend that was turning out to be quite an overhaul, a total teardown almost. Most of the hype had settled on Nirvana, a band from Seattle that played what sounded like sloppily executed songs by Boston’s Pixies, (the composition m.o.: loud part, quiet part, loud part) but instead of referencing art films Nirvana’s lyrics were about being miserable, and drilling boards into children’s heads, and rape, and what it’s like to hate yourself and want to die. Everybody loved it. Jocks and frat dudes couldn’t get enough, and cranked Nirvana at all their keggers and sang along pumping fists and belly-bumping. This sent Nirvana, who hated jocks and frat dudes, further into the dumps, even as thousands of bands reconfigured (swapped out clothes, hairstyles, guitars, and mostly drugs) and, emulating Nirvana, tried to out-brood and one-down each other in order to capitalize on the success Nirvana didn’t appear to want, by pretending not to want it either. Much of what people into this music seemed to be so down about had been addressed, if not more or less resolved over a year before, by a guy with a supercool haircut called the Fresh Prince, in a song called “Parents Just Don’t Understand�

�; whether there was anything more to it than that, this was going to be it for some time; Hollywood was onto it, mannequins in Jordan Marsh were dressed as if they drank sterno and lived under a bridge; even the Stones seemed confused, and there was no doubt that Jimmy Page was all done. But then none of that, so far as we could see, had anything to do with us. Mink got up and turned the sound down. No small feat, under the circumstances.

It is possible while in this state, this decompression, to react to multiple stimuli, but not simultaneously. Concurrent events are perceived as successive, and understood in no particular order; one artifact of reality is subsumed by another, in slow motion, and purged of information in the process, so everything is equally meaningless. So it was that to Mink and me the color of Eug’s face—alternating between a violet-blue and red-violet above the coils of a six-foot boa constrictor in a death helix around his torso—was no more alarming than Jimmy Page’s inevitable career suicide on the TV.

The post-show malaise upon him too, Eugene had not connected the snake’s initial squeeze with the more formal act of constricting until his arms were pinned to his chest and he didn’t have enough air in his lungs to alert Mink and me that he was being murdered by a giant snake, despite that that was about as obvious as a three-dimensional universe could allow. Eugene was calm, though that’s likely not the correct word to describe why he wasn’t struggling, while the snake, as far as a limbless, expressionless reptile can reveal, was panicking. Also not exactly the right word to describe why it had decided to kill Eugene. As normal thought processes returned to Mink and me by means of a fresh adrenaline bomb, we saw that the snake (I don’t think it had a name, “snake,” probably, a common enough name around Crimes’s place) had managed to pass its head into but not out of one of the nascent dreadlocks Eugene had been cultivating by continually twisting his hair and not bathing, since the day he gave up Straight Edge, months before. A glance and a whiff anyone might think there were rodents sticking out of Eugene’s head, and certainly a snake has only one way to find out. Eugene was going bluer, darker, one arm clamped at the wrist between the snake’s coils, his other hand pawing vainly at the snake’s lethally undulating body. Here we could confirm, with awe and horror, the amount of brute strength needed to separate a boa constrictor and its victim. Short of the Jaws of Life there’s not much you can do, except attempt to reason with it on some level, or kill it. Crimes kept a machete, sharp too, but—to point—there were X factors involved with whacking Eugene about the head and neck with a machete just then. The snake’s head was deeply interweaved, and it reacted to being touched by increasing pressure on Eug.

It was over when a short time later Crimes clamored in, yanked a full-length mirror from behind the couch, tossed a handful of folded paper bindles onto it, and announced that it was party time, before he took in fully what was going on, Mink there, with the machete. Eug on the floor. “Oh shit. Where’s my snake?” The snake was in a better place. Meaning anywhere but Eug’s neck. If it was lucky it had found that Habitrail of mail tubes somewhere below us that promised a steady stream of rodents, someday.

Something like that will snap you out of it pretty quickly. Yet another soundguy yammering about how you have to pay for some piece of equipment you supposedly destroyed, after the sort of show where equipment is being destroyed—no idea, just a humanoid making noises. Ten minutes or so later, he might be understood, and get an appropriate response, like, “Blood from a stone, chief.”

What we needed was a professional manager. That was the only sensible way to proceed through all this. People upset and giant snake attacks, clubs not understanding us. I asked around, followed leads, made cold-calls . . . and turned up empty. The bulk of what band managers did was done by telephone and typewriter, not in person—a fictional manager could, theoretically, do just as well. I invented a high-spirited ballbuster from Texas to stump for us. His surname, Jiggs, popped into my head while I was working my overnight shift at Store 24 thinking “gigs,” and my eyes landed on a copy of Juggs, a niche periodical. Jiggs, first name Latham, sometimes, or not, whatever, would have to comport himself as a consummately successful businessman, yet be very up front about having little to no experience managing bands, to cover any ineptitude on my part. And experience told me there was a lot I didn’t know. That’s why Jiggs had to be Texan. Because whatever the normal way of doing something is, that’s not how it’s done in Texas. This yielded mixed results. Though somewhere in one flurry of unhinged yeehaw communiqués, he cracked the Rathskeller code, where I’d failed repeatedly.

I woke up face down on a plush lawn at high noon, in the middle of a family cookout in full swing. Not my family, Mink’s. Mink’s mom, unfazed, said, “Sleep well?”

People had been stepping over and around me, my little mise-en-scène, all day. Mr. and Mrs. Rockmore were as down on this sort of behavior as any responsible parent, but simply expected you were aware you shouldn’t be sleeping on lawns until noon, rather than make a federal case out of it. Which I always appreciated. I stood up. All around were people with plates of food. Nephews and nieces in water wings frolicked in the swimming pool. The mirthful titter of children slid into my eyeballs like sewing needles.

“Fine, thank you,” I said, best I could. “Thank you for the hospitality.”

Mrs. Rockmore smiled, a loaded smile, and said, “Kitchen,” without my asking.

As I walked toward the house a country club guy out of central casting said, “My God! Yvonne! Look! It lives!” Yvonne said, “We’ll see.”

Mink was in the kitchen, caffeinating. The collars of a floral shirt that something might pounce out of winging up over his crushed velvet blazer, his summer one, what with the heat wave, rings on all fingers—mood rings, talismans, escutcheons clattering as he chucked ice into a gargantuan plastic cup—a vase, easily, and poured an entire pot of thick, jet-black coffee in after it, in stages, to preserve the ice. Then he added about a hundred lumps of no-frills granulated sugar, all the milk he could fit, and took a bottle of Pepto-Bismol down from the cabinet, for when it was time. Mink called this preparation his “criminal cup.” He drank about ten criminal cups per day. I said morning.

“Tally O!” said Mink, rapidly heaping tablespoons of sugar into the cup.

“I was asleep on the lawn. Your mother. Children.”

Mink raised a palm. “Not a problem. It’s a big lawn.” He had a sip from his cup, frowned. Added sugar, stirred more. “Anyhoo, totally normal night, all good. Except . . .”

“Ah, shit. What.”

“You might want to think about maybe making a couple calls about that little sit-chew-way-shun when you get a chance. Clear that up. Or not. Whatever. No biggie.”

“What situation?”

“The thing at the end.”

“What end. End of what.”

“You’re kidding. You don’t remember?”

“I remember we were over at the place. With that guy from the thing. And allergic to bees—her.”

“Correct.”

“Fuck-fuck showed up from wherever. With stuff from the guy.”

“Indeed.”

“And at some point we went to that house behind the thing. With what’s-his-thing. Dealer guy, with the Nazi tattoos.”

“Satan.”

“Right. But I don’t remember anything out of the ordinary.”

“Well!” Mink was in motion, always. “What happened was, I’m pretty sure someone who may or may not have been me suggested we take the hoo-ha in conjunction with the shnagger-ag. As in at the same time. We as in us, you and me, not as in everybody.”

“Yes. Solid call.”

“Why, thank you. Not my first rodeo, dahling.” Mink, who sometimes drank beer by punching a hole in the side of the can with a house key or a pen, then popping the top and letting the carbonation fire the whole thing down his throat in seconds, stirred more sugar into his cup, slugged, and made a face. He added sugar, then more. Little more after that. “Who’s the chick

with the thing and the schweee?”

“Darla.”

“Right! Darla! So Darla comes in and she’s got the whole thing going on with the things and the jingle-jangle, totally bluesy, and I take one look at her and go, ‘uh-oh, here we go.’ And sure enough, whatddaya know, she heads straight for us. And sure enough it’s all who’s got the raggle-naggle and the flooferhoff, and so on. So you, or me, or one of us says, Oh, no problem, we maybe know a guy in the Fens.”

“Death.”

“Death! Exactly. Who we can safely assume is (air quotes) ‘awake,’ to put it mildly. Right. So she goes, ‘I’ll drive.’ But then you said, ‘Okay, I’ll be right back.’ As in, yeah, right, see ya never, bye.”

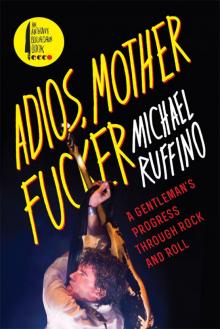

Adios, Motherfucker

Adios, Motherfucker